“Did You Learn Anything?” For my Father and Will Eisner

My Dad gave the game away. He was supposed to stick to the Iowa stubbornness that has been celebrated in word and song, and go along with code of dying: don’t talk about it, don’t mention it, just act naturally. We were spending three days with him a few weeks before he died, and he rallied to see me, my brothers and sister again, trying hard to pretend that he didn’t know why we were there, trying not to think it unusual for us to have come from different points in Washington State and Colorado to Dunlap Iowa, a town that defines ‘wide spot in the road’. We must have been just passing through, and stopped off to see the old man. That must be it. I can play along, sure. There was Dad, standing outside on the walkway to my aunt’s house where he’d been living with her and my 96 year-old Grandfather, coming home from another doctor’s visit. I walked over, smiling, it was the first time I’d been in his physical presence in a long time, and he grabbed my arm with a strength I wouldn’t have credited his body capable of, pulled me closer, and said in a weaker version of his husky whisper “Gee, it’s good to see you, Tom.” Not too many people used the word ‘gee’ anymore. He was weak, hunched from sickness and cigarettes. I helped him inside to his chair, held him to keep him from keeling over, like it was an ordinary day, just a thing I would have done anyway.

Like I said; screwed it up. He acknowledged that something was not right. After our arrival, he came out of his little bedroom with an armful of, well, junk. He’d decided he needed us to have his binoculars, old GE cassette recorder, assorted over-the-counter spy gear (my father had decided the government was not only inordinately fascinated with his pile of clipped and photocopied knowledge, but that they were coming for it, and him, any day now), and his clock radio. He didn’t need the hoard anymore, and he was sure we would. My brother Jeff and I looked at each other and well, what could you say to a dying man? No? We took it. He led us outside, his pale and yellowish body shaking with each step, to a prefab shed loaded with his old tools. For 30 years he was a cement mason, crawling on his hands and knees, making thick, rough concrete smooth. He had buckets of trowels (each with a cross carved into the handle, his mark to show the world, and borrowers, that it was his tool), his old bee gear (he was also a bee keeper, a money making business that never made much money), and assorted other treasures from his last 30-40 years. He laid it at our feet. “Take what you want, it’s all yours.” He talked of the times he smoothed the Grand Coulee Dam, how he helped build houses, buildings, walks and walls. He cussed those damn bees some more as he dragged a bee smoker from a gallon bucket. We asked him about this tool, or that job, as the day left. Dad liked talking about it, but not too much. It was getting cold, and after all, he wasn’t well.

As Dad made his way back inside, Jeff and I looked at the pile in the fading light. We didn’t say much, except to sort out what we wanted. I got the bee smoker and bonnet. Jeff got the branding iron Dad used for marking his beehives. We each took a trowel for ourselves, and Jeff took one each for his three kids. The rest would go to the family members who hadn’t showed up yet. We packed it all away again, and stored what we were taking in the car trunk. When we first picked up Dads tools that twilight, the things he used to ‘keep you kids in shoes’ (people who grew up during the depression have a thing about shoes), we had the memories of having seen and handled them before, when Dad was a younger man and we were dumb kids who sweated in 100 degree heat alongside him, getting stung by those bees. Bee herders more than keepers. Now we won’t be able to pick up one of those trowels without remembering a poor dying man who wanted desperately to give one last thing to his kids, and gave them what he had, priceless ‘junk’.

You’ll have to excuse me. When I first heard about the death of Will Eisner, so close to the death of my dad, I couldn't help but think of them as nearly one event. Both have been gone for over a decade now, but I still think of dad everyday, and of Will whenever I pick up a comic book, or sit down to write something. They both had such an impact on me, more than I ever realized. My parents divorced when I was about 7 years old, and Dad would come by once a week or so, give me my allowance (most of which I blew on comics), and during the summer, I would help him with his beehives. We would put on our coveralls, tape the sleeves and legs shut (the little bastards get everywhere) and spend hours in that 100 degree weather, in the desert that is Pasco Washington, smoking out the bees and moving the heavy hives from one row to another. It was about the only time I could spend with my Dad. It was also extra money, comic book buying money. Money to spend on Will Eisner's Spirit comic books.

You see, if we finished at a decent time, Dad would drive me to Richland, to the Bookworm bookstore so I could buy comics. He would warn me not to blow all my money, but hey! I was a dumb kid who loved comic books, I was going to buy as many comics as that $20.00 would let me. I would walk in, sticky black with sweat and honey, smelling of smoke, and head for the bathroom. That was where they kept the old comics, on shelves on either side of the toilet, from floor to ceiling. One side Marvel, the other DC, and on the floor was the old Warren magazines. I was always hunting for something in there. Sometimes it was Batman, sometimes Green Lantern or the JLA, sometimes Captain Action comics, but always I would check for the Spirit.

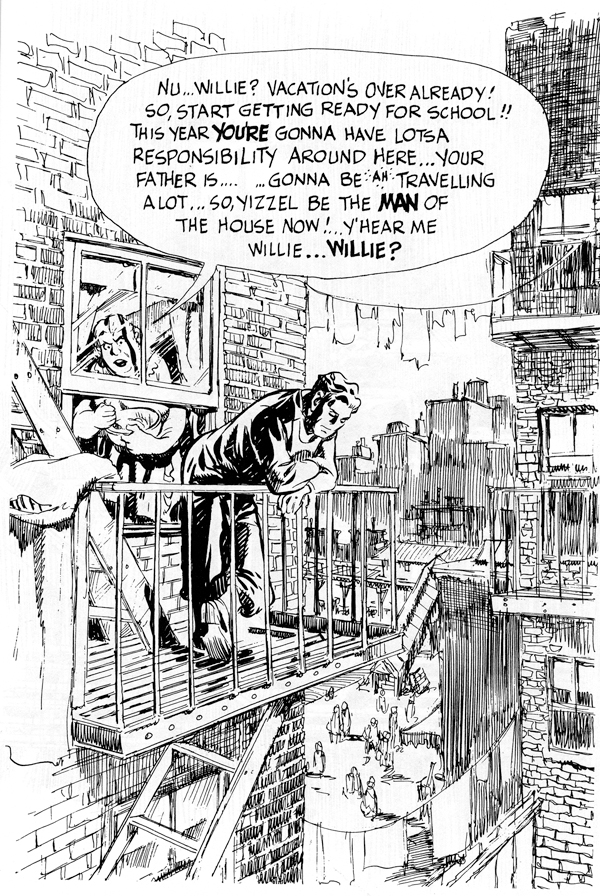

The Spirit, an all-new cover wrapped around vintage 40s-50s stories

It was 1974. I had picked up my first copy of the Spirit (#4, with a cool oil painted cover) and headed to the counter when I was stopped by my older brother: “You don’t want that.” he said. “It’s in black and white! And it’s a buck! You could buy five other comics for that!” Well, he was older, so he must be right (I was young). I put the magazine back. I didn’t give it another try until issue #9. This time I made it to the counter, bought the comic, then spent the rest of the afternoon hiding out in the refrigerator box that I had snagged from the neighbors and installed in the my room, reading the Spirit. Reading Will Eisner. I couldn’t believe it. The Spirit was a man declared dead, who wore a mask, gloves and a blue snap-brim Fedora to disguise his identity while cleaning up the underworld. Reading the Spirit was like watching old Cagney or Bogart films, the ones where Jimmy would try to go straight, but Bogey kept getting pulling him back into the life. Exotic people like Ward Heelers, sweaty city councilmen, union bosses and cheap, mob controlled building contractors walked the streets in a black and white, ink drenched, noisy, smelly, El-Train rattled, crumbling Central City, (call it what you like, even I knew it was New York) living a life that would ultimately place them in the path of the Spirit. It was serious, it was funny, and the imagination of the stories, of the art, blew my little boy mind. Each Spirit story was seven pages long, but was a window on a world I’d never heard of in tiny Pasco, WA. I was fascinated. Not only did reading the Spirit make me want to immediately pick up my pencil and draw, it made me want to know more, to find each and every issue I had missed, to know all about the Spirit and his world. This was first printed in the 1940’s? Holy geeze! Most of all, I wanted to know more about the guy who signed each story with a sweeping brush signature, this guy who told stories of the Spirit, who drew in this wonderful cinematic style, who conceived each and every seven page lesson in storytelling that was the Spirit, this ‘Will Eisner’. I was ten years old, and I’d found my calling. No, I wasn’t going to be the Spirit, I was going to be Will Eisner!

Already I was famous for my drawing. Not for being any good (I was better at it than most of the other ten year olds, but that wasn’t a huge feat). No, I was famous for drawing on anything. Tests, books, desks, tee shirts, paper bags, walls, anything within my reach (and momentarily out of the sight of adults) would end up with a Batman drawing on it. Sometimes Robin, sometimes both, depending on the amount of time I had. Now, that all changed. Now everything would have the Spirit on it. Just drawing Batman smacking the Joker was no longer enough, everything now would be a story in pictures. I started drawing whole pages of panels. I filled sketchbook after sketchbook with my Eisner swipes. Everyone had blue masks and the best hats and suits I could draw. My dad didn’t know what to make of it, but he encouraged me. He got me more sketch books when I had Eisner’d and Spirited out the last one, he enrolled me in a weekend art class to help me learn to draw something besides masked crimefighters. He even encouraged me when I was trying to save up enough to buy that first big Eisner purchase, ‘A Contract With God”.

I’d been seeing the ad for weeks (months?) in the comics. Will Eisner, the creator of the worlds coolest strip was putting out an all-new book, a BOOK, not a just a comic book, a graphic novel. Hardcovers, nice paper, all new stories about life in a tenement in the 30’s! It wouldn’t have the Spirit, (Eisner had moved past guys in masks, even if I had not) but I didn’t care, I had to have it. Signed and numbered by Will Eisner himself? Had to have it! I don’t even remember what it cost, I just remember that I had to save for it… and I couldn’t tell my mother I was getting it. You see, my mother has a habit of reverse-encouragement. The more excited I was about something, the more Mom thought it was bad, horrible, doomed to fail and just down right wrong. This applied to comics in general, and Mr. Eisner in particular. (It also applied to the Beatles and Buddy Holly, but that’s a different story). My mother couldn’t believe someone would publish such a thing, “and for HOW much? They must have seen you kids coming!” So I didn’t tell her. I reserved my copy, saved the money out of my allowance, and waited for the announcement to send it. I gave the cash to Dad on one of his weekly visits, he wrote the check, and I sent it off. And waited.

And waited.

Oh, of course, my sister ratted on me. No honor among siblings. My mother was sure I’d been ripped off. It couldn’t have been more than a couple of months, but to me it seemed like years. When it finally came, I carefully took off the wrapper, and there it was. A plain black binding with gold leaf letters ‘A Contract With God’ by Will Eisner, lettered in that great signature of his (one I copied so many times myself). Inside it was signed and numbered, just like the ad said: "#955/1000, Will Eisner." I couldn’t believe it. “Let me see that.” My mother took it and ran her finger across the signature, “I bet that’s not real.” I took the book back and went to my room to sit against the door and read it, and re-read it. The only person impressed with it was Dad.

A Contact with God was made up of four short stories. The page here is from the fourth story, the autobiographical "The Cookalein".

“Now, that’s a nice book. You should keep it nice. Handle it with care.” I could take my wannabe Eisner sketches to him and he’d put on his glasses, standing there by the door in his dirty blue Dickie work clothes, and look over each one. Even when I copied a whole Eisner story, line for line, he looked at it, over praised it, and asked me, ” What did you learn?”

“Well, I learned I’m not Will Eisner.”

He laughed. “And Will Eisner isn’t Tom Stewart. And when he was your age, he was probably copying old comic strips!”

Probably. Probably better then I could copy Eisner comic strips.

Dad helped me keep up my Eisner fix when Warren Publishing stopped publishing the Spirit by writing me a check to Kitchen Sink Press when they picked up the rights (I paid him back, of course). Dad was not a comics fan, but he would occasionally glance over an issue of the Spirit, something he remembered reading when he was a kid. “Yeah, I had ‘em all, yer Superman, Batman, the Spirit, but yer Grandmother threw ‘em out.”

He’d shake his head, I’d shake mine (grandmothers!). As I grew older, I would discover other artists like Neal Adams, Alex Toth, a whole wealth of them, but I never forgot Eisner (my Adams swipes looked like Adams inked by Eisner, lots of shadows and ink). Dad would look over my pages, praise them, and point out the panels he liked best, almost always the Eisner swipes. The man had taste.

After high school, I moved away, then moved back. I started college and took art classes, but had switched to mostly acting classes (posters I designed for the plays looked like Eisner-lite). Dad left the cement masons due to arthritis in his knees. His health was failing, and he started getting, well, a bit paranoid. He pulled me aside one day to inform me he’d solved the Kennedy assignation. He had proof, Kennedy was killed by a Cuban hit man who’d fired 26 shots at him. I said I’d hoped they got their deposit back, because, well, that must have been one lousy hitman.

Dad didn’t speak to me for two weeks.

I got a scholarship to an acting school in Seattle, and had to leave in a week. I packed up everything I could, and left the rest for my brother to gather up for me. When I saw my dad to say goodbye, I gave him a drawing I did. It was a portrait of me, in a blue mask and fedora... of course.

Soon after, Dad, no longer feeling safe in a state that according to his reading of biblical prophecy was going to slide into the ocean any moment, left Pasco, Washington to move to Dunlap, Iowa where his family still lived. We wrote letters back and forth, mine filled with tales of the school, and little drawings, his with tales of government surveillance and dire news of the end of all life… any day now. We talked on the phone, but didn’t see much of each other, both too busy (or poor) too make the trip to Iowa or Seattle.

Years later, I finally met Will Eisner. I’d written him a few letters, telling him of a play I’d written and performed that was dedicated to him. His letters back were always kind and gracious. When I met him in San Diego, I reminded him of our correspondence. He laughed, shook my hand, and signed the old Spirit comics I offered him. As he commented on the stories, I told that I’d once copied an entire Spirit story. ‘Really?’ He leaned forward and peered at me through his glasses,

“Did you learn anything?”

“I learned I was no Will Eisner.” Will laughed like my father had.

After my Dad passed in May of ‘04, my brother found all the letters I’d ever written him. Jeff was going through Dad’s things, and here, among the end of the world pamphlets and ‘how to not pay your taxes or license your car’ books, were all the envelopes, notes, cards that I’d sent him. In an honored position, tucked inside a cardboard holder to keep it safe, was that drawing I’d made of myself as the Spirit. On the back was written, in my Dads spider scrawl, ‘Tom as Will Eisner’. Close enough.

Both are gone now, my Father and Will Eisner. I thought of both of them last night, as I worked on a play based loosely on Will, and one that I know my dad would love to have seen preformed. I was no Will Eisner, but I was never meant to be. I was John Stewart's son. And that's what I have learned.