"So, What Kind of Guy WAS Mike Sekowsky?"

First of all, a confession. As a kid, (a very young, very ill-informed kid) I didn't care much for Mike Sekowsky's artwork. There, it's said, so let it be writ against me in the Book of Life. It seemed clunky, blocky, and just, well, strange. (I thought the same thing about Kirby... death threats can be sent in care of this blog, but you will be mocked) Most of what I knew of art was what I learned tracing Neal Adams and Will Eisner, and Mike didn't fit well into either of those molds.

I've spent the last month or so calling his friends, (and a few people who might fit that description only reluctantly), digging through my collection, and that of friends, in order to get a better view, a better idea of the man behind the JLA, the NEW Wonder Woman (the first time she would be labeled as ‘new’, but not the last), and the art that everyone has an opinion about.

Mike Sekowsky was a man that didn't talk about himself much, not at all if he could avoid it. A large man, tall and quiet, very shy in his relations with other people, Mike Sekowsky was a hard man to get to know, just ask his friends. "Mike... was hard to compliment. For the first six months he knew you, you couldn't get him to look you in the eye" Mark Evanier, comics writer and Sekowsky friend told me. "He didn't take compliments well...", mostly mumbling thanks and looking for a way out of the whole awkward situation.

Mike started in comics in the early 40's, probably at Timely. His first assignment for the young Stan Lee was drawing a strip called ZIGGY PIG and SILLY SEAL, one of many forgettable funny animal comics coming out at the time. He soon graduated to other strips at Timely, such as Gus the Gnome, Black Widow, Young Allies and Captain America. He worked at Timely on and off through the 1940's.

Sekowsky probably worked at just about every company putting out comics during the 40's and 50's. Under his own name, and helping out other artists, like his long time friend, artist Joe Giella:

"Yeah. It was the first job, inking a story at Timely, which is what Marvel was called back then. I was a kid 17-18... a six pager, I think, and I lost it, somewhere on the subway. I thought Stan was gonna fire me! This guy, big guy, comes up to me and say's, 'I'll pencil it for you, give me the script.' He penciled it, and I inked it, and Stan was happy. Saved my ass on that one! It was Mike Sekowsky, and he wouldn't take any money for it, not at all. He said, 'Just do it for someone else sometime.' We became real close after that. That was Mike."

And a lot of other artists owed Mike a thanks for similar saves. Joe again: "Yeah, he did that a lot. He ghosted lots of pages..."

Mark Evanier: " There's a lot of stories where right in the middle of say, a Gil Kane story or something, it will suddenly become Mike Sekowsky for a few pages.... Mike had a great respect for artists. If you were an artist and you said you were in trouble, He'd pick up a pencil and start helping out right there. Never worried about money, didn't care about that."

Mike worked for Timely, (then Atlas) throughout the 50's on everything that came along, from westerns to teen comedy, to romance, to funny animals.

Joe Giella, " You name it, he did it. Mike could do it all. He was fast, and GOOD, all good stuff."

Now, just how fast was Mike? Mark?

"Well... I'll give you the example of Sekowsky and Jack Kirby. Let's say you gave Mike and Jack the same script page, and two hours to draw it. If you came back in a hour, Jack would have half the page drawn, but Mike wouldn't have started. There might be some guide lines, a few sketchy lines, but that'd be it. Mike would spend the first hour and a half planning the page, and the last half hour drawing it. And it would be terrific stuff.

You would think an editor would like a fast artist, but there were times when Mike could be too fast for some. At least one editor looked at the pages, shook his head and said, "You're rushing, Mike. Slow down, take your time." So next time, Mike would finish the pages, then hold onto them for a few days before turning them in. And, of course, the editor would say, "Much better. See what you can do when you take your time?"

And how was inking Sekowsky? Joe again;

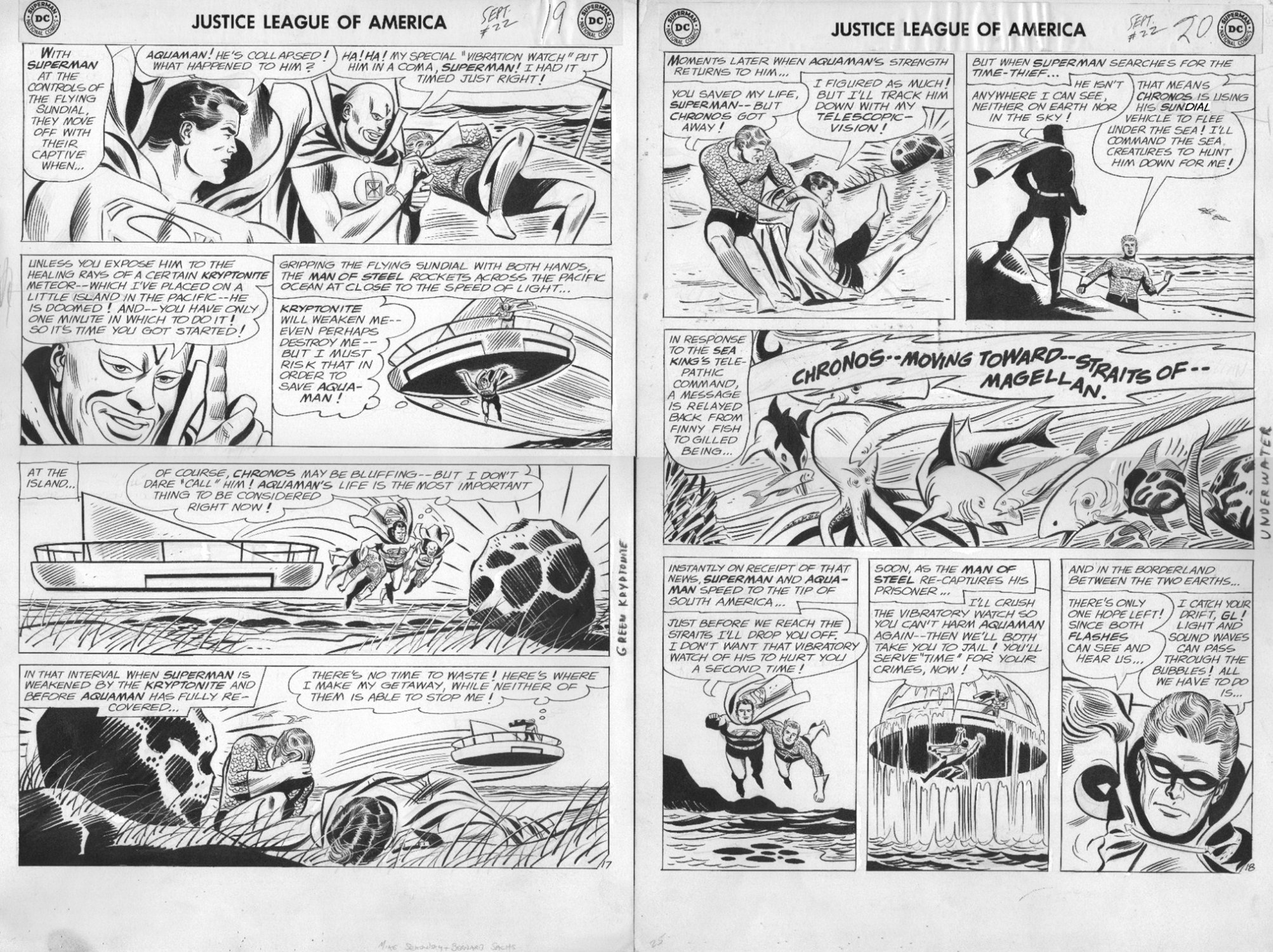

"Mike's pencils were dark... He had a very deliberate, strong style. Good control over the pencil, everything there. The problem was the drawing wasn't as accurate as one would want. His proportions would be a little off. A good inker could fix that, no problem. But boy, was he a layout man, that's where he really excelled. He could layout a story, and utilize a panel to it's fullest. Wouldn't fake backgrounds, not at all. Terrific designer, great layout man."

All of which would help him out on the series he's most well known for, The Justice League of America. Mike had been working for DC since the early 50's, penciling on their war, romance, space, and mystery titles. Everything except the Superhero titles, it seems. In 1959, after successful revivals of the Flash and Green Lantern, Julie decided to bring back the Justice Society in a new form, the Justice League of America. Gardner Fox would write, and Sekowsky would pencil.

Vintage Sekowsky JLA art. With bonus JSA!

Why was Mike chosen for the title? Well, Mike was probably one of the few artists to navigate between almost all the DC editors at the time. The editors were always happy to have Mike on a title. Why?

Mark: "Because they knew it'd come in on time, or earlier."

Joe: "Mike was a speed merchant. He was fast, fast. In the time I did one page, Mike could do four. Not inking, just penciling. You need to make a deadline, you call Mike, and he was right there. " Julie Schwartz had most of his stable busy on other books. Gil Kane was busy on the Green Lantern re-launch; Carmine Infantino was on the Flash, with Murphy Anderson and Joe Giella inking both of them. It only made sense for Julie to turn to one of his most reliable artists, Mike Sekowsky. And Sekowsky was ready for the challenge.

How did Mike feel about his signature title, the JLA? Mark Evanier:

"Mike enjoyed it at first. It was a challenge that he liked, figuring out where everything would go. But after awhile, he got bored with it, and he felt the writing wasn't as good. Then, when DC changed the page size (shrinking it), Mike felt he just couldn't draw it with the same quality."

Mike went on to draw some 66 issues of the JLA: 66 issues of hundreds of super heroes, wearing hundreds of different costumes. He quit several times before they found someone to replace him. Artist Dick Dillin took over soon after Mike left the title, staying on the book for a run even longer then Sekowsky's.

Mark again: "When I told Mike that Dick had passed away, he said, "Yeah, that book would kill anybody."

There's been a bit of controversy about Sekowsky's art on the JLA, and other super hero titles. Some fans felt his art just didn't fit the super hero mold. Mike drew in different styles, but for DC, this was his ‘DC’ style, his ‘Alex Toth’ style. Mark Evanier; "Well, I think Mike drew the way he did deliberately. He could draw in other styles... but this was his take on the DC super hero house style. And he was very proud of the way he drew."

Hell, I'D buy it! And I did, as a back issue 30 years later.

Mike Sekowsky became an editor in 1968, taking over the titles that had been edited by Jack Miller. Mike had wanted to make the move into editorial for a while (maybe to have a little more control over his work), and the promotion of Carmine Infantino to art director, then to Editorial Director (later Publisher), cleared the way. Overnight, several artists were promoted to editors. Mike was assigned Metal Men, and Wonder Woman.

Wonder Woman, at the time, was one of DC lowest selling titles, limping along on memories of its former glory. DC had found out earlier, after considering canceling the title, that the deal management had made with William Moulton Marston, the creator of Wonder Woman, back in the 1940s gave the rights back to his estate if DC stopped publishing the book. So to keep those exclusive rights in house, (and at that time there was some TV interest) DC decided to publish at a loss.

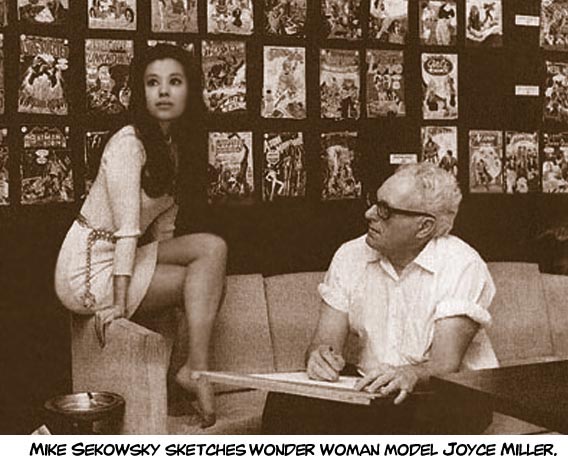

Enter Mike Sekowsky. Mike had been playing around with an idea for a series for about a karate chopping female and her Asian guide. He injected this into Wonder Woman, stripping her of her traditional costume and powers, and having her train in the martial arts. Sales increased (how much we don't know, records are spotty at best) and so did controversy about the change. Older fans were unhappy at the wholesale changes, but new fans were attracted to the new, hipper style. During the run, Sekowsky replaced Denny O'Neil as writer, writing several issues (some of the best of the run) before leaving the book.

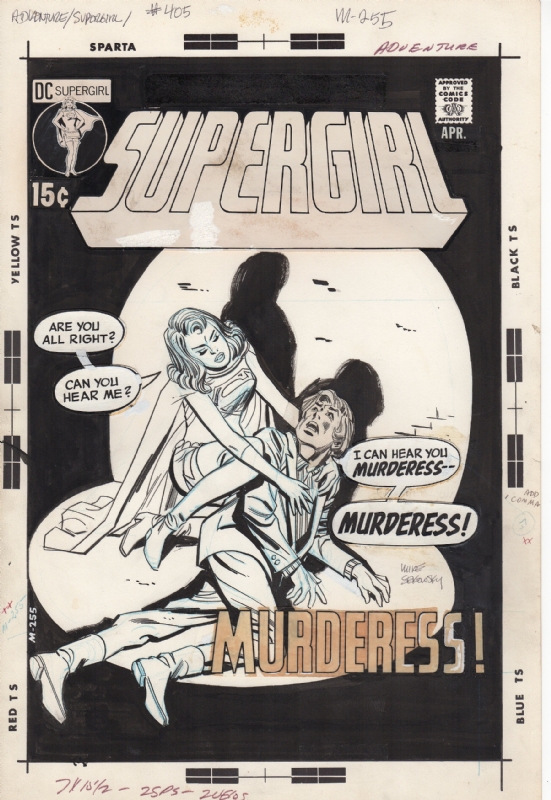

Sekowsky Supergirl

Mike had also taken over Supergirl, trying to bring some life into that series. But he couldn't quite make lightning strike twice. Without Sekowsky, WW reverted back to her old powers and costume, to be more in line with a planned TV series. After working on Supergirl for several issues, Mike left the title, and left DC.

Why?

One DC editor at the time said Sekowsky was a great guy, especially when you got to know him. But, when he was mad...

So, Mike had a temper?

Mark: "Oh yeah, he sure did. "

What would set him off?

Mark: "Well, Mike had an ego. He was a big, loud guy when it came to his work. He was thought he was good, (and he was) and he didn't think he was appreciated as much as he should have been.. and he was probably right a lot of times..."

After a long running, love-hate battle with management, with Mike feeling that his work and input was not appreciated, Mike left. Around this time, Mike also started have some problems, both with his health, (he'd developed diabetes) and alcohol.

Did Mike have a drinking problem?

Mark Evanier:

"Yeah, yeah, that's true, Mike did have a problem with that. He'd pretty much licked it by the time he moved out here (West Coast) But, yeah, it was no secret.

Mike was big, pale, very pasty guy. He wasn't doing all that well with his health... Mike had his good days and his bad. I mean, 30-35 years in the business, you're bound to have times when things just don't go right."

Mike went to work for Marvel, penciling the Inhumans and Submariner/Dr. Doom. But his work was not up to Sekowsky standards. Sickness and alcohol took its toll. Bill Everett was called in to redraw parts of an Inhumans issue. Mike left comics to move to the west coast and into animation design for studios like Hanna Barbera.

Mike produced new comic stories after ending his run at DC and Marvel in the 1970's, mostly lots of Hanna Barbera comics for the foreign market, and later one shots for DC, (including a little heralded return to the JLA) and a few stories for independent publishers, like Eclipse.

Mark Evanier: "Mike could be very bitter about his time in comics. He didn't want to talk about it much."

But he still had his sense of humor.

Mark: “At Hanna-Barbera, he put a sign up over his desk. At the time, there were a lot of new guys coming in -- guys around my age -- who remembered his work from the JLA or WONDER WOMAN. They kept coming up to him to meet the great Mike Sekowsky and they all said the same thing -- "I didn't like your art when I was a kid but now I love it." It got to be a running joke around the studio. Mike procured a number dispenser, like they use in a bakery, and he put it up over his cubicle with a sign that said, "Take a number to tell me how much you used to hate my work but you love it now."

And what about the famous 'nude' JLA story? Seems Evanier had a sketchbook, like a lot of fans, that he would give to artists to draw in. Mark decided not to ask for any specific drawing, but just to let the artist draw whatever came to mind. One artist drew a couple of characters, one being a nude woman. The next also drew a nude. By the time it got to Sekowsky, "I figured Mike would draw a naked somebody and that would be it. But when I got the book back, I found he had drawn this long, 12 page JUSTICE LEAGUE story, with Wonder Woman naked and the men of the JLA fighting over her. “He said he'd been waiting twenty years to draw that story."

Mark: "That was one thing we never really saw, was his humor. Mike had a wicked, really twisted sense of humor. There's some of that in Jason's Quest, a little of it in Wonder Woman, but we never saw a whole story of it... it's really to bad."

In 1981, Mike's friends tricked him into going to the San Diego Convention, to watch Alex Toth receive the Inkpot Award, the annual award given to honor achievements in the field of comics. Mike was reluctant to go, reluctant to see his old co-workers again. He sat through the tribute to Toth, then heard his name announced.

Mark: "There was this big ovation for Mike, as soon as his name was announced. He broke into this great big smile. The award meant a lot to him, but I think the ovation meant even more."

As he passed by Julie Schwartz's table, Mike leaned down to whisper something to his old editor.

"Afterwards I collared Julie and said, 'All right, what'd Sekowsky say to you?' Julie smiled:

'My page rates just went up."

Mike died in 1989.

PS: There is still, somewhere, an unpublished four-issue Green Arrow/Black Canary mini-series drawn by Mike Sekowsky, maybe sitting on DC's shelves somewhere, gathering dust.

Don't worry, we're looking.

Thanks must be given to the many patient people who extended help with this article, such as: Dr. Jerry Bails, Mark Evanier, Joe Giella, Denny O'Neil, and Dr. Michael J. Vassallo. Thank you.